A handful of influential writers cast long shadows over the fantasy genre. The core fantasy reader has always been fond of the familiar trope, eager to revisit comfortable archetypes. The influences of Lovecraft and Tolkein loom especially large in that landscape. Both writers can claim that unique privilege afforded to literary greats–their names have been turned into adjectives. Yet the themes of what define the “Lovecraftian” and the “Tolkeinesque” could not be more different; the despairing cosmic nihilism of the Cthulu mythos is the antithesis of the heroics of Middle-Earth.

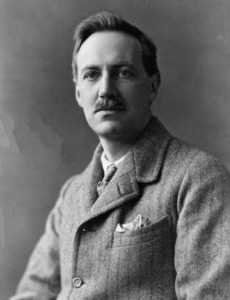

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany

But both authors are united in one thing. They acknowledged the tremendous influence of one writer on their style: Lord Dunsany.

Lord Dunsany is almost unknown today, but in the early decades of the twentieth century he was among the world’s most popular writers. He published at least eighty books in his life, plus eight collections of poetry. At one time he had five different plays running simultaneously on the New York stage. His appeal transcended the modern constraints of genre, and his contemporaries and associates included names like Rudyard Kipling and William Butler Yeats. Yeats was in fact to edit some of Dunsany’s work, and personally solicited plays for the Abbey theater. Dunsany, said Yeats, “transfigured with beauty the common sights of the world.”

Dunsany was born to the Anglo-Irish nobility. The ‘Lord’ was not an affectation but a fact; he held the second-oldest peerage in all Ireland. More rightly named Edward Plunkett, he elected to publish his work under his more poetic-sounding title. His first book’s printing was financed out of his own pocket. Such was its success that he would never again need to foot his own bill.

An examination of his life looks like the biography of a fictional character. He fought in the Boer War, saw front-line duty in World War I, and was active in the defense of England during the Battle of Britain in World War II. He was a devoted safari adventurer and big-game hunter; he campaigned for a variety of political causes and twice ran for parliament, serving also as an elector. Raised in London, he spent time in both England and Ireland, and was active in the latter country’s literary social scene. Dunsany exchanged letters and hob-knobbed with Arthur C. Clarke, H.G. Wells, and George Bernard Shaw.

Dunsany’s fame was mainstream. At the turn of the twentieth century, the modern conception of fantasy as a distinct genre or publishing category did not exist. Fantastic works certainly existed; gods and miracles have been in literature since prehistory. But Dunsany was an innovator. He was a key figure in establishing what we now describe as “secondary world” fantasy–works taking place in fully imagined settings with no links to any traditional mythology or cosmology. Reflecting on a collection of such stories published 1905, Dunsany observed: “In The Gods of Pegana I tried to account for the [unique] ocean and the moon. I don’t know whether anyone else has ever tried that before.”

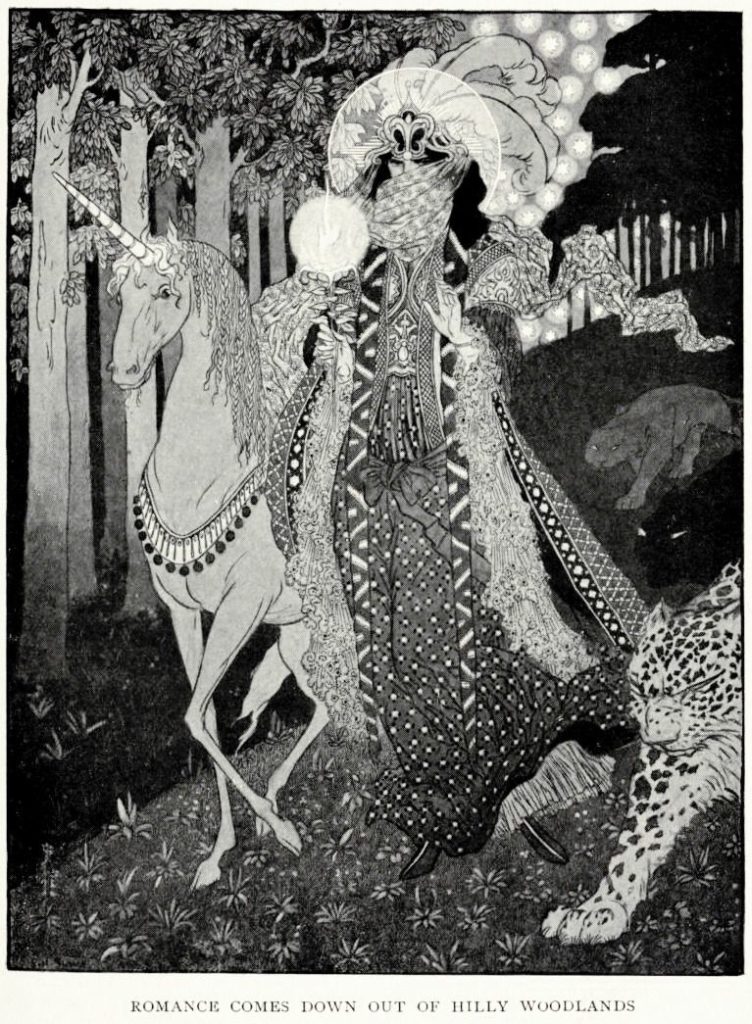

Romance, one of the titular gods of Pegana. Dunsany’s works were almost exclusively illustrated by Sidney Herbert Sime, a coal miner, born to poverty, who financed his own way through art school.

Accounting for all the SF authors who have cited Dunsany’s influence could probably fuel a doctorate. Howard, Le Guin, Wolfe, Clarke, Moorcock, Vance, Gaiman, and Eddings are just a few of the names who’ve explicitly named their debt and admiration. Filmmakers like Guillermo Del Toro have also expressed enthusiasm for Dunsany. But H.P. Lovecraft is perhaps uniquely breathless in his praise.

“Truly,” said Lovecraft, “Dunsany has influenced me more than anyone else except Poe–his rich language, his cosmic point of view, his remote dream-world, & his exquisite sense of the fantastic, all appeal to me more than anything else in modern literature.”

Lovecraft lamented to Fritz Leiber that he went for a time into a sort of Dunsinian madness, producing only derivative works, imitations of his literary idol. In his letters of that period, he despaired that he would never discover a truly original voice, and was instead doomed only to write knock-off pastiche. Tolkein, for his part, is said to have handed out copies of Dunsany’s work to those who assisted with the assembly of the Silmarillion as a touchstone of influence and style.

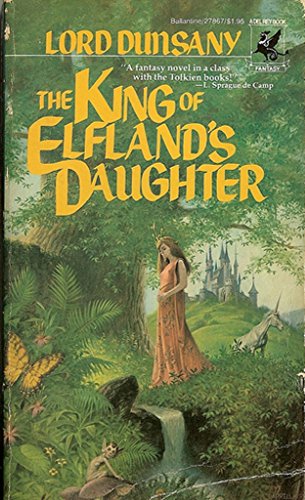

Yet despite his sterling reputation a hundred years ago, by the end of the twentieth century Dunsany was more or less forgotten. There have been revivals, of course–influential fantasy editor Lin Carter was a fan of Dunsany’s, and he did much to keep the fire of Dunsany appreciation alive, re-issuing several stories in his seminal Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. But nowadays Dunsany is not really part of the genre conversation. He’s one of those names that floats around in the aether, every once in a while getting trotted out again when someone like a Neil Gaiman can be troubled to write an introduction to one of his re-issued books.

The King of Elfland’s Daughter, 1976 Ballantine edition. Touted by L. Sprague de Camp as “a fantasy novel in a class with the Tolkein books.”

I’d seen those books floating around, but I had never actually read any Dunsany myself. The time had come, I figured, to change that.

The question was where to start. There are at least a hundred different books with Dunsany’s name on them. Thankfully, there is something of a consensus on the question. If there is one Dunsany work that has stood the test of time, it is undoubtedly The King of Elfland’s Daughter. It did not make waves on release, but it is consistently the most remarked upon and most re-issued of Dunsany’s books in the years since his 1957 death.

The opening is a familiar one, drawing on Celtic and British legend. The sleepy hamlet of Erl sits beside the border with the realm of Faerie–called here Elfland–and its people decide that they desire some of its magic for themselves. Indeed, they wish to be ruled by a magic lord. Thus does the thoroughly un-magical lord of Erl send his son on a mission across the boundary to claim an enchanted bride. This is a riskier mission than it may at first appear, for the King of Elfland is a powerful wizard, and in his eternal realm, time passes far slower than in the mortal world. Should the young heir of Erl linger there too long, years might pass in the span of a day.

A sidebar: fans of Tolkein are willing to admit that the Lord of the Rings suffers somewhat from a slow start. Much has been written in defense of Tom Bombadil and the stately opening of the Fellowship of the Ring, but the fact is, the plot does not really get started until the Council of Elrond some considerable distance into the book. One must reach the Mines of Moria before the adventure is on in earnest. That initial slog through the countryside of Middle-Earth has vanquished many a reader’s attention span. Speaking frankly, back when I was working as a reader for a literary agency, I would have put the Fellowship in the reject pile, if it had come across my desk with no knowledge of The Hobbit, or what lay ahead later in that volume.

By contrast, The King of Elfland’s Daughter opens with a bang. We are but pages into the text before the young heir–the lyrically named Alveric–has set off on his quest. His first step is the domicile of an ancient sorceress, who forges for him a sword woven together with thunderbolts, knit from the lightning she keeps captured in her gardens. It is a magic sword, and a sword for breaking magic: But fear the three runes of the elf-king, warns the witch, for these are magics unparalleled, and even a sword of thunder cannot best them.

Alveric plunges headlong into Elfland, sword in hand, quite literally cutting a path to the castle of the king. There await four eternal sentries, men born from magic, and battle is waged. Alveric slays them all, and the princess held captive there, Lirazel, is so besotted with this adventurous stranger that she agrees to be wed immediately. What follows is a familiar story: Lirazel meshes poorly with the strange customs of the men of Earth, and though she gives to Erl its magic heir, she is soon enough seduced home by the magic of her mighty father. Alveric begins a fruitless quest to find once again the boundary of Elfland, accompanied by vagrants and madmen, thwarted continuously by the Elf-king’s power.

All this was long before Tolkein and Jordan and Dungeons & Dragons and all their imitators that have ground the tropes of elves and magic into the ground. There is a real excitement and earnestness in these sections of Dunsany’s novel. For my money, tropes always feel freshest when you trace them back to their source, and this is fairly high up the chain. Unfortunately, I was not quite so keen on the second half of the story as the first.

Once Alveric is off on his second, fruitless quest, the book’s pacing slows down considerably. Alveric’s son Orion grows up and becomes a hunter; trolls and other creatures from Elfland come to Earth and learn of its strangenesses. Alveric wanders–and wanders. Orion hunts more, eventually hunting unicorns. The people grow uncomfortable with magic. Lirazel laments. It is all very stately, and the pages keep on turning, with no appreciable forward movement in plot.

How much one will enjoy the back half of the book depends in large part on how much one enjoys Lord Dunsany’s prose. That he is a poet is immediately apparent. His capacity for names of both character and place is especially good, the equal of Tolkein’s, albeit without the linguistic heft behind it. The book feels closer to the nineteenth century than the twentieth, in terms of its style–a classical lyricism infuses the pages, an attention to the cadence of sentences and the color and sense of imagery. Where Lovecraft is often guilty of purple prose and adverbial excess, Dunsany is more restrained. But even this Victorian-flavored restraint may be florid by the tastes of a modern reader who is more comfortable with a Sanderson or a Patterson.

Also dating the book’s style–but perhaps enjoyably so–is the greater flexibility this period had for narrative voice. These days, third or first person narration tends to be quite limited, in the sense that it is anchored to character viewpoint. Dunsany is not afraid of omniscient-narrator interjections. Often these asides are there to provide a bit of levity or wryness to what is otherwise a rather serious work. Aside from the well-trod myths from which it is borrowing, the originality is largely in the splendor of magic worked, and the grandeur of Elfland itself, its timelessness often described in breathless detail.

But in truth, the great weakness of Dunsany’s masterpiece lies in its ending–it proceeds irrespective of anything that has been done by most of the leading characters. Despite getting loaded up with a second round of enchantments and Chekov’s-gun advice from the witch, Alveric never makes it across the border to Elfland again to have his foreshadowed confrontation. Despite his deeds hunting unicorns and the seductive calling that lies in his magic blood, Orion never crosses the border to Elfland. Instead it is the heartfelt plea of princess Lirazel to her nigh-omnipotent father that ends the tale. Which would be fine–if Lirazel did not largely vanish from the narrative until this moment.

Faced with her desire to reunite with her family, the mighty king agrees to use the last of his peerless runes to expand the boundaries of Elfland–absorbing the entirety of Erl into its eternal kingdom, a process which is described quite beautifully, but ends up feeling like something of a deus ex machina. The resolution does not seem to follow the adventurous promise of the early narrative–and indeed, despite carrying it about with him, and despite the elf-king previously resurrecting his magic knight, Alveric is never to use his lightning sword again after first claiming his bride.

I came away impressed with Dunsany’s talent as a writer, but ultimately unfulfilled as regards the plot. I expected climax and confrontation, but received meanderings and tone poem. Perhaps if the beginning of the book were as mellow and slow-paced as what followed, I would feel differently. I think that the book would have been best as a novella–were the middle bits cut in half, or perhaps even to a third, there would not be so many flipped pages with so very little happening in the way of forward action. Less time to get antsy also would have meant less time building up expectations of an ultimate resolution. As it is, the book is full of magic, full of the wonder of place, but somewhat light on plot.

As such, though Dunsany’s talent is indisputable, and his influence hard to overstate, his classic novel was not for me an unambiguously enjoyable product. His successors, perhaps, have done him better in plot–even if he may be their better in verse. I plan to eventually pick up some of his shorter works, where he might be forced to keep the plot more front-and-center, with less room to get lost in the enchanted weeds.

Perhaps I am simply more of a sword-and-sorcery reader–more naturally a Robert E. Howard devotee than a Dunsany enthusiast. It seems that it is not the details of the plot that matter most to the 18th lord of Dunsany, but rather to impart the feeling of the ethereal and the mystic: to transport his reader to the experience of a different world, and a different time, much like the men of Erl are literally transported at the conclusion of the text.

Leave a Reply